Sixth Attempt at Explaining the Importance of

Children's Books

...and why grownups should read

them.

...and why grownups should read

them.

Like the title says, I've tried writing this post

five times. I keep sliding into dead ends and inconsequent

thinking.

Why, why, why? When I try to write on this

subject, I end up being trite ("They're classic! Alice in Wonderland!

Beatrix Potter!) or sentimental ("I cried when Old

Yeller died!") or preachy ("Think of the life-lessons in The

Little Match Girl"!). Then my own mind turns traitor and

asks, "Well, Mary, what about serious books? Crime

and Punishment, The Gulag Archipelago, Madame

Bovary, Jude the Obscure?" Cowed, I back away from writing

the post, feeling like an intellectual lightweight. (And I've

read Crime and Punishment, and Jude the Obscure.)

But I return to the subject, because I think it

matters, and seems worth a sixth attempt.

There are certain kinds of insight and thought

that can, IMO, best be expressed in a children's story. Because

it's a forum with unique qualities:

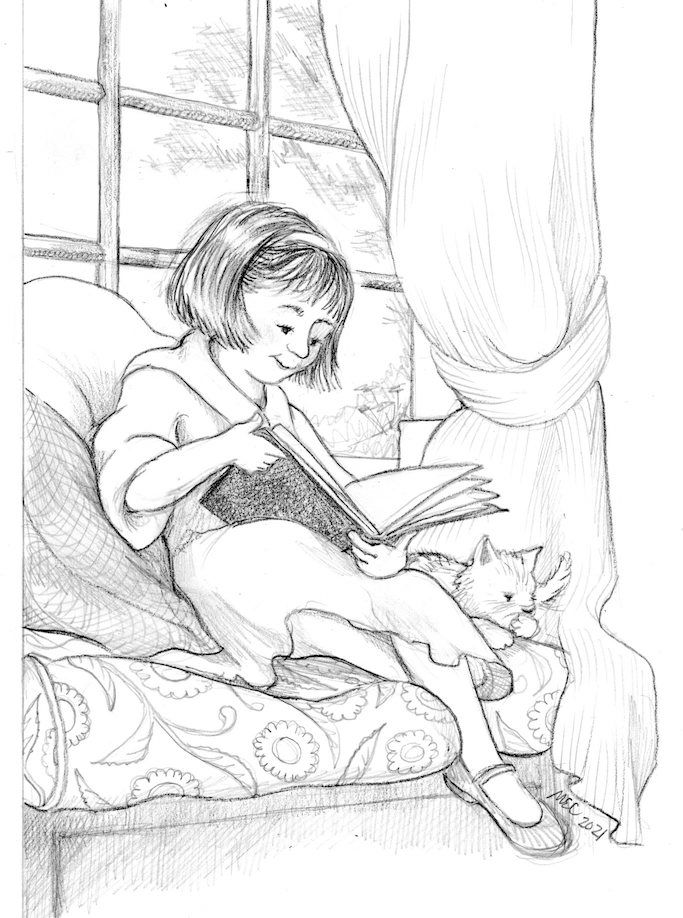

- Safe space. Everybody

opening the book knows nothing irredeemably awful will happen

to the protagonist. This is where I've stumbled in earlier

attempts to write, because excluding the darkest side of life

feels like a cheat, like an artist using only half the

palette. Two different friends, over the years, have asked me

to please kill off a couple of my characters, and I haven't

done it yet. Because what I cherish in literature for the

young is what I sometimes need myself: a safe space. If you've

ever had a few hours to spend in a beautiful spot with no task

to complete, no bills to pay, no feud to fight, and where

benevolence surrounds you - that's the feeling I allow myself

to settle into with a children's book. Oh, there will be

suspense, but you won't encounter the dread of a

gruesome ending. That dread is a feature of much adult

reading. I remember vividly my then-teenage son coming in and

waking me up at one a.m., elated because he'd finished Lord

of the Flies and NOT everybody died. He'd had a

harrowing read. There's a time and place for a harrowing read,

but it's not every time and every place. The

range of possible outcomes in serious literature includes the

very dark part of the fictional color spectrum. The presence

of the dark colors can cut off the brighter end of the

spectrum. Not many authors can manage a full palette. In

children's literature, we're free to read with a cheerful

expectation of a good outcome, once expressed in a gospel

tune: "I read the end of the book, and we win." The happy

assurance of a good outcome can revive hope in a hopeless

heart, and there's something to be said for that.

- Simplicity. Children's

literature, like the parables of Christ, has a simplicity that

eases the first reading, then reveals depth and more depth

upon further readings. Things that can decorate adult fiction

can't be relied on in juvenilia. Small children famously don't

"get" sarcasm, so making points with snark may not make the

point at all. The canny kid-lit author won't depend on

it. (There are exceptions - Lemony Snicket books come to

mind.) And very young readers are so busy processing their

first encounter with suspense or mystery, they'll miss adult

nuances buried in syntax or clues tucked into a description.

The subtlety gets noticed on a second or third reading, but

the book can't depend on that, either - it had better be a

good read on the first pass. So, if I can't make my point with

hints, sarcasm and nuance, how will I make it? In a book for

kids, I must have a gripping story and compelling characters.

Everything else is gravy.

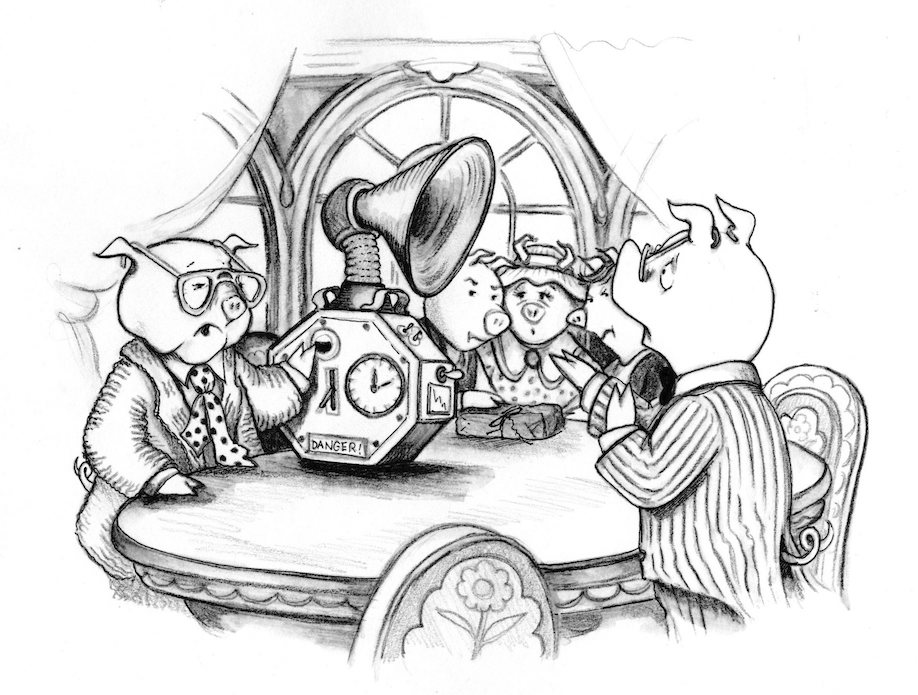

- Magic, Miracles and

Coincidence. Obviously, the impossible is part of adult

literature - that's why there's science fiction and, I add

with tongue in cheek, True Romance. ;) But I get to use it

differently in books for young readers. I get to be

matter-of-fact about miracles. I get to posit the Easter

Bunny, or a winged mailman, or talking

pigs, with a fairly straight face. And the audience will

cut me that slack. If I do my job well, they'll say yes, Mrs.

Coons, we'll go with you to a place you've named Pigville, and

we'll accept the rules that govern it. Pigs ride bicycles and

type with their trotters. When one of my (adult) writer

friends pointed out that my villain's lightning machine

wouldn't really work, I replied, "My concern isn't what's

possible, just what's consistent in my make-believe world.

That's the beauty of writing about talking pigs." She subsided

. Some of the

"coincidences" that have graced my life would look like

cheating-to-advance-the-plot if I inserted them into a

manuscript. I think kids are smarter than grownups about this.

They'll accept the chance sighting of the White Rabbit and go

with Alice down the rabbit hole; they'll tumble into the

wardrobe with Lucy, and then examine every closet in the house

to see if maybe, just maybe, there's a local portal to

Wonderland or Narnia. I'd argue we'd all be better off with a

bit of that attitude. If we cultivated eyes that see every

daisy as a miracle, if we allowed ourselves, like G. K.

Chesterton, to believe in fairies. To try, like the white

queen in Lewis Carroll's Alice, to "believe six

impossible things before breakfast."

. Some of the

"coincidences" that have graced my life would look like

cheating-to-advance-the-plot if I inserted them into a

manuscript. I think kids are smarter than grownups about this.

They'll accept the chance sighting of the White Rabbit and go

with Alice down the rabbit hole; they'll tumble into the

wardrobe with Lucy, and then examine every closet in the house

to see if maybe, just maybe, there's a local portal to

Wonderland or Narnia. I'd argue we'd all be better off with a

bit of that attitude. If we cultivated eyes that see every

daisy as a miracle, if we allowed ourselves, like G. K.

Chesterton, to believe in fairies. To try, like the white

queen in Lewis Carroll's Alice, to "believe six

impossible things before breakfast."

If we did, we'd be better able to

believe remarkable things about ourselves. Somewhere deep inside,

each of us cherishes the hope that we are special and that,

against all odds, someone sees our specialness. Children's books

take this as a given, and shine a bright light on the path the

hero must take, then give that hero help with serendipitous

meetings and surprising bits of good fortune dumped in his lap.

Such things are the bread and butter of kiddie lit. Adults find

them easy to dismiss. We forget that the odds against each of us

existing at all are overwhelming, that we should thank God for the

day we get to live in, and for the blessings on our plate.

That's my point. Children's books encourage us to

believe good things, impossible things, can happen, and that

they can happen to us. To you, to me. Allow me to close

with a paragraph from my new book, Feathergill's

Fabulous Emporium. This describes my main

character:

The fact is, Elizabeth had no idea how

important she was. It is unpopular, nowadays, for the narrator

to step into the story to tell the reader things, but it seems

necessary in this case, because

our character has no idea... Elizabeth is still walking around

Granger's Green without a clue that the story is all about

her. And while we're at it, we

will add that every person reading this book is in something

of the same predicament. Most of us don't know the importance

of our own story - and in Elizabeth's case, it is almost too late...

Well, clearly you'll have to read the book to find

out what happens. But rest assured, Elizabeth's story holds a

happy ending. Let's consider that this is true for each of us.

If you find this difficult, may I suggest picking up a good

children's book?

For other thoughts on life & literature, sign up for my

blog here.

As always, thanks for reading.

. Some of the

"coincidences" that have graced my life would look like

cheating-to-advance-the-plot if I inserted them into a

manuscript. I think kids are smarter than grownups about this.

They'll accept the chance sighting of the White Rabbit and go

with Alice down the rabbit hole; they'll tumble into the

wardrobe with Lucy, and then examine every closet in the house

to see if maybe, just maybe, there's a local portal to

Wonderland or Narnia. I'd argue we'd all be better off with a

bit of that attitude. If we cultivated eyes that see every

daisy as a miracle, if we allowed ourselves, like G. K.

Chesterton, to believe in fairies. To try, like the white

queen in Lewis Carroll's Alice, to "believe six

impossible things before breakfast."

. Some of the

"coincidences" that have graced my life would look like

cheating-to-advance-the-plot if I inserted them into a

manuscript. I think kids are smarter than grownups about this.

They'll accept the chance sighting of the White Rabbit and go

with Alice down the rabbit hole; they'll tumble into the

wardrobe with Lucy, and then examine every closet in the house

to see if maybe, just maybe, there's a local portal to

Wonderland or Narnia. I'd argue we'd all be better off with a

bit of that attitude. If we cultivated eyes that see every

daisy as a miracle, if we allowed ourselves, like G. K.

Chesterton, to believe in fairies. To try, like the white

queen in Lewis Carroll's Alice, to "believe six

impossible things before breakfast." ...and why grownups should read

them.

...and why grownups should read

them.