How Books Talk to Each Other

Johannes Gutenberg

changed the world by putting more words in the hands of more

people. But a thousand pages in the hand do not have the worth

of one in the reader’s mind. The magic happens between the

page and the brain.

_____________________________

In 2018,

scientists discovered the interstitium - the largest

organ in the human body. It’s a fluid highway that wraps and

connects all the other organs, performing feats of service in

the space between. Turns out a lot of work happens between the

organs we’ve always known about, done by a near-invisible

organ that went undetected for centuries.

So many things

happen in what looks like blank space between tangible things.

If you plunk out the notes of “Amazing Grace” on a piano

without the proper spaces, the song is unrecognizable. The

empty space is essential.

We’re told to

“read between the lines” when we need to grasp that more is

going on than meets the eye. In the Book of Proverbs, there’s

a lot of room for pondering in the blank space between the

halves of a verse. Take Solomon’s first attributed proverb,

Proverbs 10:1: “A wise son makes a glad father; but a

foolish son is the heaviness of his mother.” Two fairly

obvious points, but wait! The space between the two statements

gives you enough to ponder for days – in that space lies the

difference between fathers and mothers, wisdom and

foolishness, gladness and heaviness. The simple verse isn’t

simple at all when the reader stops in the space between the

two thoughts, looks ahead and behind, and ponders. Multiple

lessons lie between the lines, waiting to ambush a thoughtful

observer.

Of course this

applies to reading in general.

Maybe you’re like

me: you have one book in the upstairs bathroom, one in the

downstairs, two or three bedside. You probably have some way

of choosing reading material: my husband acts vigorously on

recommendations; my parents belonged to one of those

book-a-month clubs. I have a friend who finds an author he

likes and systematically reads their every book. Some rely on

best-seller lists. My books come to me washed up on the shores

of used book shops and thrift stores. I’ve always trusted that

it’s God arranging my curriculum. Time and time again, exactly

what I needed to read showed up exactly when I needed to read

it.

Here’s how this

worked in the summer of 2001, when my older son was about to

leave for college, and I was aching at the impending end of

the family unit. Upstairs, I was reading John Eldredge’s The

Journey of Desire (if you don’t love John Eldredge, you

and I will have to talk), while downstairs sat Philip

Kunhardt, Jr.’s 1970 reminiscence, My Father’s House,

like a ticking bomb.

The two books talked to each other

all summer, using the space between my ears as their

parlor. My

Father’s House held surprises. Author Kunhardt, a fellow

New Jersey-ite, was a managing editor of Life magazine

– a publication delivered weekly to my childhood home and

which I, starved for new reading material, devoured hungrily

upon arrival. He grew up in the woods in Morris County – me,

too! He wrote this book after surviving the kind of heart

attack that killed his father in 1963. It is a very personal

book.

It became that to

me, too. Kunhardt’s aim is to describe the upbringing his

father bestowed on him. Gruff-but-caring, adventurous,

instructive, free-wheeling but hands-on. A marvelous

upbringing, a storybook upbringing. The kind of upbringing my

own father would have had, (because he grew up in the same

place, at the same time), had he only had a decent

relationship with my grandfather. Today I searched out my copy

of My Father’s House to ascertain particulars of

publication, and found myself in tears, just as in 2001.

But those tears

were a function of the Eldredge book, a book that encourages

good people trapped in shoulds and oughts to

consider their hearts, to examine them for what they love, and

to embrace that love as God’s gift. The Journey of Desire

(retitled Desire in recent editions) handed me

permission to love Haydn symphonies and old British murder

mysteries and the complex designs of good silk scarves. And,

to embrace the goodness in the Kunhardt book, which I would

not have done without it.

The Journey of

Desire opened up my thinking like the key on a sardine

tin. Before reading it, I had thought depriving myself was a

necessary reflexive exercise, to be done any time I liked

/wanted /enjoyed something. As a result, I squelched things

God put in my heart. These two books worked like two friends

come in to do an intervention, chipping away at assumptions

I’d held and lies I’d believed. I wept all summer, reading the

two books and contemplating their admixture of kindness,

mercy, parental love, and beauty. They stitched up a corner of

my soul I didn’t know was ripped. By the time Jimmy left for

college, I felt prepared for the change, prepared to carry on,

peaceful.

Neither book would

have had its effect without the other, yet neither one said,

outright, what I derived from it. The magic happened in the

space between the books.

Words on a page

set up a spate of synapse-jumps in the brain. Reading more

than one book multiplies the effect of the jumps, because the

world of more than one writer’s brain gets added to the world

of the reader’s. Stereos is a Greek word, sometimes

translated “established,” denoting something confirmed from

more than one source. We get “stereo” from it. This tag-team

reading has a stereos effect – two different streams

of thought converge and contribute to each other, the effect

multiplied not arithmetically, but exponentially, as I ponder

what they say. Pondering the written word acts like the

interstitium. It provides the space for the words on the page

to perform their appointed tasks, allowing the whole to become

more than the sum of the parts.

Whether you’re

reading one book or ten, what have you been pondering?

Click here to

subscribe.

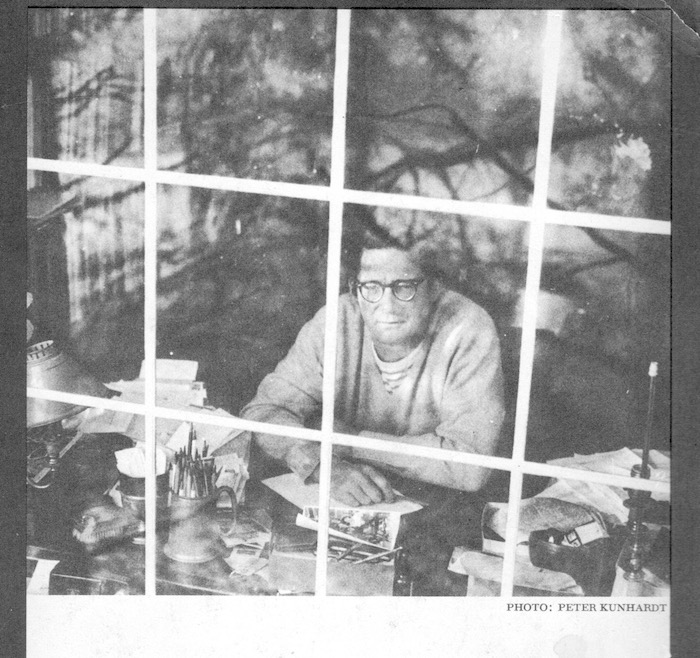

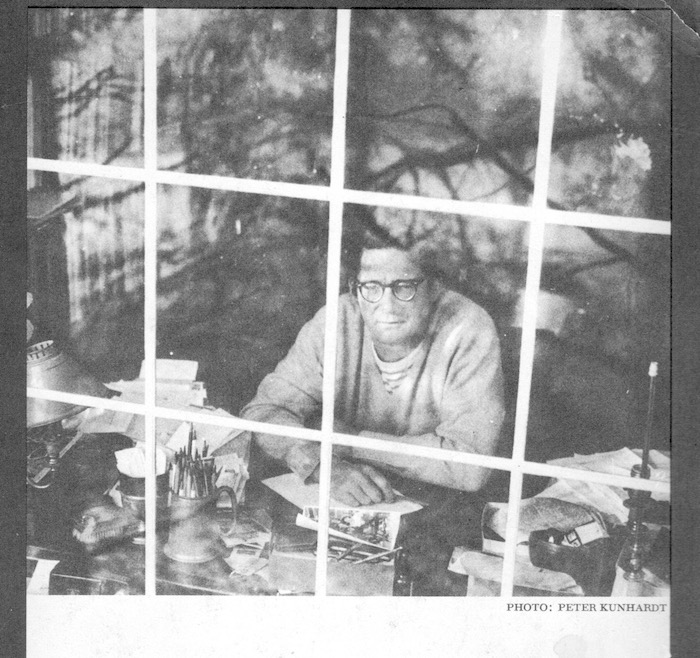

Here's

the back cover photograph from My Father's House,

here, a masterful portrait, IMO. Kunhardt and my dad looked a

lot alike.