TINY BITS OF HISTORY

The great bulk of the past was created by people about whom we know nothing. People whose lives have slipped through the cracks.

But these untold millions leave a trail, like mouse droppings, in old newspapers, cook books, catalogues. Etiquette books and old advertisements reveal, through florid prose and wild claims and now-preposterous rules, how people of their day thought. What was life like? How would you fasten your shoes with a button hook? How to “black” the wood burning stove you cooked the family dinner in? To shave with a straight razor? To give serious thought to the shape of your visiting card, and the significance of folding down one corner? The history we’ve never read is made of these details, daily tasks performed by people who left no mark.

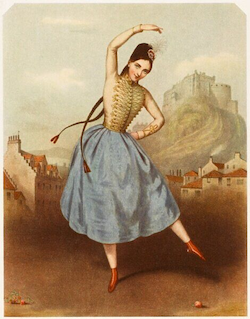

Sometimes I inhale a whole book, just to absorb the feel of its time. Loving old mysteries, I picked up Arthur Train’s 1920 Mr. Tutt’s Case Book - a friendly fictional jaunt through New York justice in the very early 1900s, revealing the cunning and the innocence of the day. Then I read Meade Minnigerode’s The Fabulous Forties, a 1924 history of the 1840s. It gave me an overview of the raucous, candlelit decade that culminated in the Gold Rush. It also, unintentionally, provided a glimpse of the smug superiority of the author’s 1920s. She is smug about the boisterous politics of the “Tippecanoe and Tyler, Too” presidential campaign, about the 1840’s fascination with dancer Fanny Elssler’s “fine figure,” (I include a picture), about 1840s table manners and "the besetting sin with Americans of all ranks" - eating from the blades of their knives! Her complacency is the mark of the Roaring Twenties in which she lived and moved and had her being, unaware of the Great Depression lurking on her doorstep.

Just as handwriting is hard to disguise, just as DNA and fingerprints are impossible to imitate, so the decade in which a book was written leaves its mark on the writing. The author is steeped like a teabag in his day and time, and his output reveals his era. The thinking has a flavor.

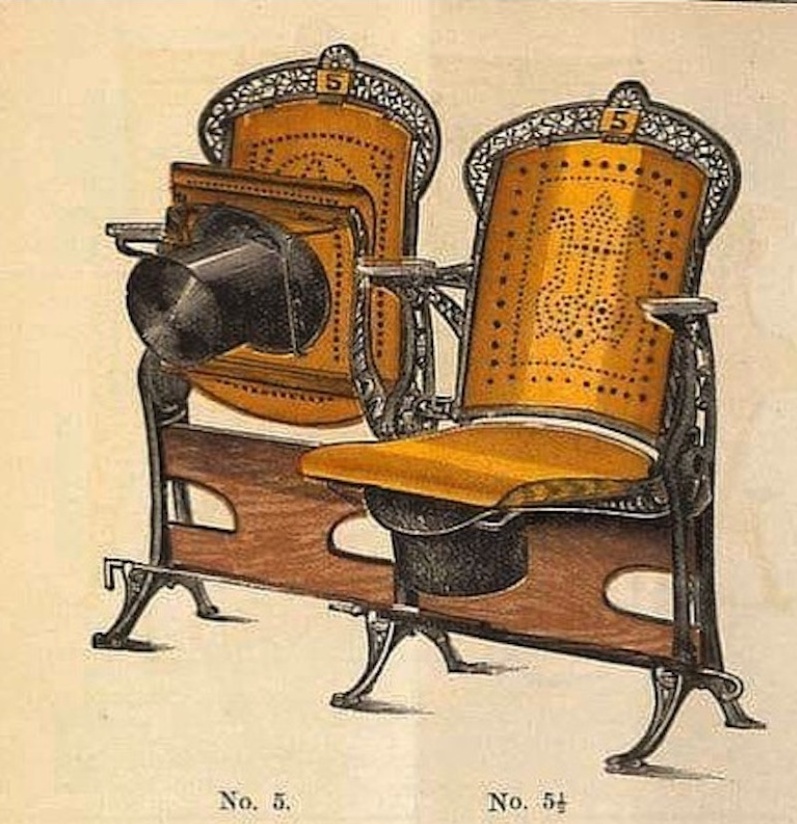

I'm always trying to taste the flavor of other ages. Maybe that’s why I’m fascinated by silver thimbles, by the curling iron that crimped a 1930s coiffure, by the rack under each seat in our church, made for the gentlemen to stow their hats. I have my grandmother’s silver-filagreed perfume bottles. These were the commonplaces of life in past decades, the daily essentials of forgotten days used by people who made their mark on life, if not on history. They still carry the scent of their decade.

I curate a private collection of historic incidents that remind me how small things can loom large, how large things can be forgotten. It's a quirky list, and may give you whiplash, but here are four of my favorite entries:

Rex Stout – who wrote the famous Nero Wolfe mysteries – had a sister, Ruth, who wrote the semi-famous Ruth Stout’s No-Work Gardening Book. When they were children, their fascinating mother safeguarded her time to read by the tactic of offering to wash the face of every child who interrupted her in her library. And look how her children turned out! She’s not famous – but I think she should be.

The good ship Mayflower is preserved today as a barn in Buckinghamshire, England. The beams were re-used after it was sold for scrap in 1624. Hundreds of tourists visit it every week. Until recently, I never knew.

That handy kitchen appliance, the blender, was originally known as the Waring Blendor, named after band leader Fred Waring, who invested $25,000 in the invention in 1933, and demonstrated it when his band toured the country. Without him, you likely couldn’t make your morning smoothie.

The largest fire in American history happened in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, WHILE the great 1871 Chicago fire raged. On the same night. The Chicago fire killed about 120 to 300 people; the Peshtigo fire, fifteen hundred to two thousand. On the selfsame night. A death toll comparable to the Titanic, and most of us don’t know about it.

How much have we forgotten? Heaven knows, there's more history than historians can cover.

We study the larger-than-life historical figures, not the little guy, the man-on-the-street. Understandably, because who could? But the great leaders – Alexander the Great, Gandhi, Tolstoy - riding the crest of history’s waves have, beneath them, the swell of thousands and millions of everyday people, heroes by virtue of living their lives, raising their kids, doing their jobs, crimping their hair. These are the people Jesus spoke about in the Beatitudes, and they make up the bulk of history, even if they don’t earn a paragraph in history books. I'm seeking their scent when I study the corners of history.

Each of our lives has a web of connections, its own cluster of coincidences and amazements. Personal histories. We have our own set of events that marked our course, that crop up as the oft-told stories making our kids roll their eyes, that have served as guiding lights in dark moments. They may never grace a history book, but they contribute to the pool of history, a pool that includes the famous, the infamous, and the meek. You and me, not to put too fine a point on it.

Jesus said, in the Beatitudes, that the poor in spirit are blessed, that the meek will inherit the earth. He himself, I could argue, is among them - for among all famous people, who "did" less than Jesus? A short life, lived in obscurity and ended in shame (until the Resurrection.)

I'm here to say, small things matter. They accrue, they add up. And God notices; He cares. He keeps accounts we don't maintain on earth, and in His cosmic scales, the little person weighs as much as the famous one. And so, I study the small things, and rejoice in their flavor.

As always, thank you for reading, and for commenting. Have a happy New Year, rejoicing in life's small miracles.

Click here to subscribe.